12 KiB

Training with Self-Play

ML-Agents provides the functionality to train both symmetric and asymmetric adversarial games with Self-Play. A symmetric game is one in which opposing agents are equal in form, function and objective. Examples of symmetric games are our Tennis and Soccer example environments. In reinforcement learning, this means both agents have the same observation and action spaces and learn from the same reward function and so they can share the same policy. In asymmetric games, this is not the case. An example of an asymmetric game is our Strikers Vs Goalie example environment. Agents in these types of games do not always have the same observation or action spaces and so sharing policy networks is not necessarily ideal.

With self-play, an agent learns in adversarial games by competing against fixed, past versions of its opponent (which could be itself as in symmetric games) to provide a more stable, stationary learning environment. This is compared to competing against the current, best opponent in every episode, which is constantly changing (because it's learning).

Self-play can be used with our implementations of both Proximal Policy Optimization (PPO) and Soft Actor-Critc (SAC). However, from the perspective of an individual agent, these scenarios appear to have non-stationary dynamics because the opponent is often changing. This can cause significant issues in the experience replay mechanism used by SAC. Thus, we recommend that users use PPO. For further reading on this issue in particular, see the paper Stabilising Experience Replay for Deep Multi-Agent Reinforcement Learning. For more general information on training with ML-Agents, see Training ML-Agents. For more algorithm specific instruction, please see the documentation for PPO or SAC.

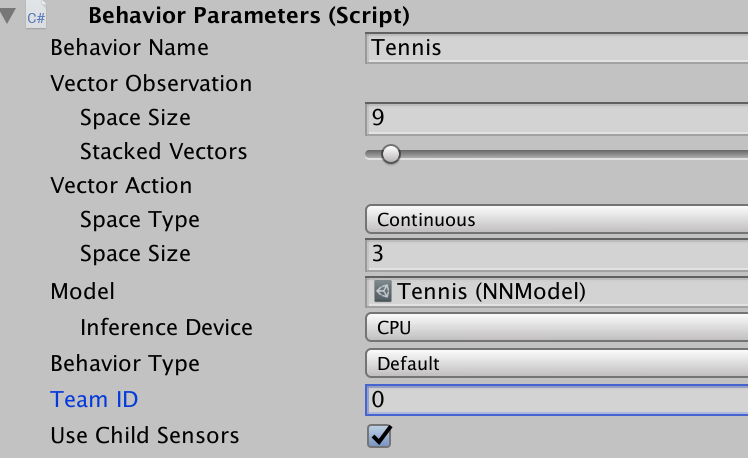

Self-play is triggered by including the self-play hyperparameter hierarchy in the trainer configuration file. Detailed description of the self-play hyperparameters are contained below. Furthermore, to distinguish opposing agents, set the team ID to different integer values in the behavior parameters script on the agent prefab.

Team ID must be 0 or an integer greater than 0.

In symmetric games, since all agents (even on opposing teams) will share the same policy, they should have the same 'Behavior Name' in their Behavior Parameters Script. In asymmetric games, they should have a different Behavior Name in their Behavior Parameters script. Note, in asymmetric games, the agents must have both different Behavior Names and different team IDs! Then, specify the trainer configuration for each Behavior Name in your scene as you would normally, and remember to include the self-play hyperparameter hierarchy!

For examples of how to use this feature, you can see the trainer configurations and agent prefabs for our Tennis, Soccer, and Strikers Vs Goalie environments. Tennis and Soccer provide examples of symmetric games and Strikers Vs Goalie provides an example of an asymmetric game.

Best Practices Training with Self-Play

Training with self-play adds additional confounding factors to the usual issues faced by reinforcement learning. In general, the tradeoff is between the skill level and generality of the final policy and the stability of learning. Training against a set of slowly or unchanging adversaries with low diversity results in a more stable learning process than training against a set of quickly changing adversaries with high diversity. With this context, this guide discusses the exposed self-play hyperparameters and intuitions for tuning them.

Hyperparameters

Reward Signals

We make the assumption that the final reward in a trajectory corresponds to the outcome of an episode. A final reward greater than 0 indicates winning, less than 0 indicates losing and 0 indicates a draw. The final reward determines the result of an episode (win, loss, or draw) in the ELO calculation.

The reward signal should still be used as described in the documentation for the other trainers and reward signals. However, we encourage users to be a bit more conservative when shaping reward functions due to the instability and non-stationarity of learning in adversarial games. Specifically, we encourage users to begin with the simplest possible reward function (+1 winning, -1 losing) and to allow for more iterations of training to compensate for the sparsity of reward.

In problems that are too challenging to be solved by sparse rewards, it may be necessary to provide intermediate rewards to encourage useful instrumental behaviors. For example, it may be difficult for a soccer agent to learn that kicking a ball into the net receives a reward because this sequence has a low probability of occurring randomly. However, it will have a higher probability of occurring if the agent learns generally that kicking the ball has utility. So, we may be able to speed up training by giving the agent intermediate reward for kicking the ball. However, we must be careful that the agent doesn't learn to undermine its original objective of scoring goals e.g. if it scores a goal, the episode ends and it can no longer receive reward for kicking the ball. The behavior that receives the most reward may be to keep the ball out of the net and to kick it indefinitely! To address this, we suggest using a curriculum that allows the agents to learn the necessary intermediate behavior (i.e. colliding with a ball) and then decays this reward signal to allow training on just the rewards of winning and losing. Please see our documentation on how to use curriculum learning here and our SoccerTwos example environment.

Save Steps

The save_steps parameter corresponds to the number of trainer steps between snapshots. For example, if save_steps=10000 then a snapshot of the current policy will be saved every 10000 trainer steps. Note, trainer steps are counted per agent. For more information, please see the migration doc after v0.13.

A larger value of save_steps will yield a set of opponents that cover a wider range of skill levels and possibly play styles since the policy receives more training. As a result, the agent trains against a wider variety of opponents. Learning a policy to defeat more diverse opponents is a harder problem and so may require more overall training steps but also may lead to more general and robust policy at the end of training. This value is also dependent on how intrinsically difficult the environment is for the agent.

Recommended Range : 10000-100000

Team Change

The team_change parameter corresponds to the number of trainer_steps between switching the learning team.

This is the number of trainer steps the teams associated with a specific ghost trainer will train before a different team

becomes the new learning team. It is possible that, in asymmetric games, opposing teams require fewer trainer steps to make similar

performance gains. This enables users to train a more complicated team of agents for more trainer steps than a simpler team of agents

per team switch.

A larger value of team-change will allow the agent to train longer against it's opponents. The longer an agent trains against the same set of opponents

the more able it will be to defeat them. However, training against them for too long may result in overfitting to the particular opponent strategies

and so the agent may fail against the next batch of opponents.

The value of team-change will determine how many snapshots of the agent's policy are saved to be used as opponents for the other team. So, we

recommend setting this value as a function of the save_steps parameter discussed previously.

Recommended Range : 4x-10x where x=save_steps

Swap Steps

The swap_steps parameter corresponds to the number of ghost steps (not trainer steps) between swapping the opponents policy with a different snapshot.

A 'ghost step' refers to a step taken by an agent that is following a fixed policy and not learning. The reason for this distinction is that in asymmetric games,

we may have teams with an unequal number of agents e.g. a 2v1 scenario like our Strikers Vs Goalie example environment. The team with two agents collects

twice as many agent steps per environment step as the team with one agent. Thus, these two values will need to be distinct to ensure that the same number

of trainer steps corresponds to the same number of opponent swaps for each team. The formula for swap_steps if

a user desires x swaps of a team with num_agents agents against an opponent team with num_opponent_agents

agents during team-change total steps is:

swap_steps = (num_agents / num_opponent_agents) * (team_change / x)

As an example, in a 2v1 scenario, if we want the swap to occur x=4 times during team-change=200000 steps,

the swap_steps for the team of one agent is:

swap_steps = (1 / 2) * (200000 / 4) = 25000

The swap_steps for the team of two agents is:

swap_steps = (2 / 1) * (200000 / 4) = 100000

Note, with equal team sizes, the first term is equal to 1 and swap_steps can be calculated by just dividing the total steps by the desired number of swaps.

A larger value of swap_steps means that an agent will play against the same fixed opponent for a longer number of training iterations. This results in a more stable training scenario, but leaves the agent open to the risk of overfitting it's behavior for this particular opponent. Thus, when a new opponent is swapped, the agent may lose more often than expected.

Recommended Range : 10000-100000

Play against latest model ratio

The play_against_latest_model_ratio parameter corresponds to the probability

an agent will play against the latest opponent policy. With probability

1 - play_against_latest_model_ratio, the agent will play against a snapshot of its

opponent from a past iteration.

A larger value of play_against_latest_model_ratio indicates that an agent will be playing against the current opponent more often. Since the agent is updating it's policy, the opponent will be different from iteration to iteration. This can lead to an unstable learning environment, but poses the agent with an auto-curricula of more increasingly challenging situations which may lead to a stronger final policy.

Range : 0.0 - 1.0

Window

The window parameter corresponds to the size of the sliding window of past snapshots from which the agent's opponents are sampled. For example, a window size of 5 will save the last 5 snapshots taken. Each time a new snapshot is taken, the oldest is discarded.

A larger value of window means that an agent's pool of opponents will contain a larger diversity of behaviors since it will contain policies from earlier in the training run. Like in the save_steps hyperparameter, the agent trains against a wider variety of opponents. Learning a policy to defeat more diverse opponents is a harder problem and so may require more overall training steps but also may lead to more general and robust policy at the end of training.

Recommended Range : 5 - 30

Training Statistics

To view training statistics, use TensorBoard. For information on launching and using TensorBoard, see here.

ELO

In adversarial games, the cumulative environment reward may not be a meaningful metric by which to track learning progress. This is because cumulative reward is entirely dependent on the skill of the opponent. An agent at a particular skill level will get more or less reward against a worse or better agent, respectively.

We provide an implementation of the ELO rating system, a method for calculating the relative skill level between two players from a given population in a zero-sum game. For more information on ELO, please see the ELO wiki. In a proper training run, the ELO of the agent should steadily increase. The absolute value of the ELO is less important than the change in ELO over training iterations.

Note, this implementation will support any number of teams but ELO is only applicable to games with two teams. It is ongoing work to implement a reliable metric for measuring progress in scenarios with three or more teams. These scenarios can still train, though as of now, reward and qualitative observations are the only metric by which we can judge performance.